For all you writers out there like myself, you probably know how hard it is to edit your own work, especially when it comes to typos. Your brain automatically fills in the blank—and corrects errors—as you read over each line in your head, making the little boogers near impossible to see. Now, I’m not suggesting that you use this method as a substitute for hiring a professional for the majority of your editing; in fact, you absolutely should be doing that before you even consider publication. However, I’ve come up with a solution that does a pretty darn good job of the proofreading process at least, and it even helps some with line editing. Best of all, it’s FREE if you already own Microsoft Word.

Word has a nifty little tool built in called text-to-speech (TTS). It’s no surprise that this feature is included, but since it’s not part of the standard toolbar at the top (I myself was unaware of it until after I stumbled across it in a Google search), many people miss it.

Activating Text-to-Speech

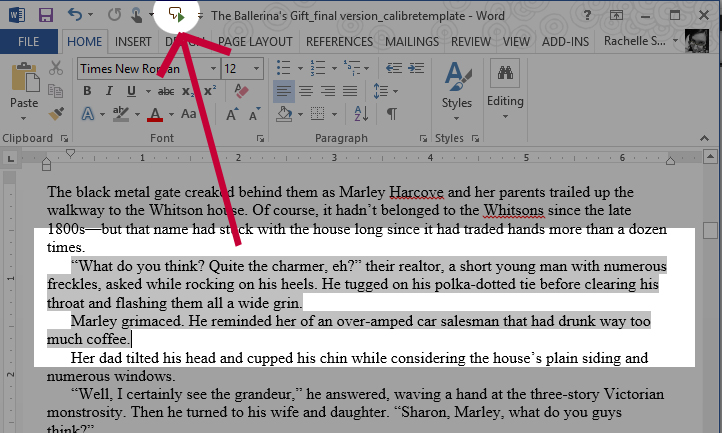

Next to the quick access toolbar at the top, you’ll find a drop down arrow. If you click it, a list of customizable commands for the toolbar will pop up. After clicking More Commands, make all commands available, then scroll down until you find the Speak option. Select it and click Add. Click OK to save the changes, then you’re all set. It should now show up at the top.

Now all you have to do is highlight the text you wish to have it read by selecting it in the document and clicking the shortcut for the Speak tool from the toolbar at the top. It looks like a comment bubble with a play arrow at the bottom right-hand corner.

For a more thorough step-by-step guide, you can check out the how-to article on Microsoft’s site.

Why This Works Better Than Other Methods

I’ve seen plenty of suggestions for other methods, such as printing out your book or reading it backwards to catch errors like this. And while those do work well for spotting the majority of the issues, particularly the print-out method, they have one major flaw: you’re still the one reading your own writing, which means you’re relying on your brain to pick up on its shortcomings through what you see. And as I’ve already established, your brain is generally pretty biased when it comes to reading your own writing. By having an unbiased source, such as the computer, read the text for you, you’re instead free to listen to the text. And believe me, it’s much easier to hear errors than it is to see them. My proof?

In my most recent book, I had nearly a dozen beta readers and two editors go through it, not to mention having revised it several times myself. But despite that, after using the text-to-speech feature, I caught over twenty additional typos and errors that all of us missed. And let me be clear about this, because this is a really important point. I’m in NO way knocking my betas or editors. They are fantastic, and my book wouldn’t even be half of what it is without their input. What I am suggesting is that we’re all human. And as such, we have flaws. One major flaw with our brains—well, it’s actually a huge upside that is an adaption for survival if you think about it—is that it’s completely wired to read things correctly, even when they’re not. It has a tough time picking up on all the errors in writing, which is why we editors have to work so hard to develop a keen eye for potential problems. Case in point is this well-known example:

I cdnuo’lt blveiee taht I cluod aulaclty uesdnatnrd waht I was rdanieg. The phaonmneal pweor of the hmuan mind. Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it dseno’t mtaetr in waht oerdr the ltteres in a wrod are; the olny iproamtnt tihng is taht the frsit and lsat ltteer be in the rghi t pclae.

So before you hit the “send” button on the final draft of your manuscript, whether you’re self-publishing or submitting your work to publishers, agents, or even magazines, give this method a try. Your betas, editors, publisher, and readers—not to mention you, yourself—will be glad you did.